Abraham Lincoln was an attorney, ferryman, postmaster, storekeeper, and politician. He was a common man who accomplished uncommon feats. Lincoln had no administrative experience before becoming President and had no meaningful military experience. Yet, he became an avid strategist, able to direct field leaders and issue precise orders.[1] Lincoln’s deft leadership spanned the course of eight different lead generals and four years of conflict that ultimately led to the preservation of the Union. Lincoln’s leadership resulted in a legacy of innovation and change that still permeates our society today.

EXPAND YOUR KNOWLEDGE

External Links to Additional Resources

Lincoln’s leadership is best viewed through the lens of transformational leadership. Transformational leadership is a process in which a leader increases their associates’ awareness of what is right and important, raises motivational maturity, and moves individuals beyond their own self-interests for the good of the group, the organization, and society.[2] “The goal of transformational leadership is to ‘transform’ people and organizations in a literal sense — to change them in mind and heart; enlarge vision, insight, and understanding; clarify purposes; make behavior congruent with beliefs, principles, or values; and bring about changes that are permanent, self-perpetuating, and momentum building.”[3] In today’s climate, The Judge Advocate General’s Corps must display dynamic leadership in order to create disciplined and legally enabled Airmen and Air Force organizations that advance the mission. Lincoln provides a historical blueprint to grow our leadership principles.

Inspirational Motivation

Lincoln’s challenge during the Civil War was great. The Confederates were compelled to fight for their freedom and to protect their homes, but Lincoln’s task was to continuously motivate northern soldiers to fight for something that was much less understood and appreciated — the preservation of the Union.[4] This became more difficult as years passed and casualties mounted. Lincoln navigated these impediments by articulating a clear vision to his followers and convincing them to buy-in.

The ability to inspire, the first element of Transformational leadership.

Through four years of conflict, Lincoln employed eight different generals to lead the Army of the Potomac: Irvin McDowell, George McClellan (twice), John Pope, Ambrose Burnside, Joseph Hooker, George Meade and Ulysses S. Grant.[5] The first seven suffered from poor tactics, the inability to effectively pursue Robert E. Lee’s army, and the lack of understanding of how to properly utilize a vastly superior Army. Interactions with two generals — McClellan and Grant, demonstrate examples of Lincoln’s ability to inspire, the first element of Transformational leadership.

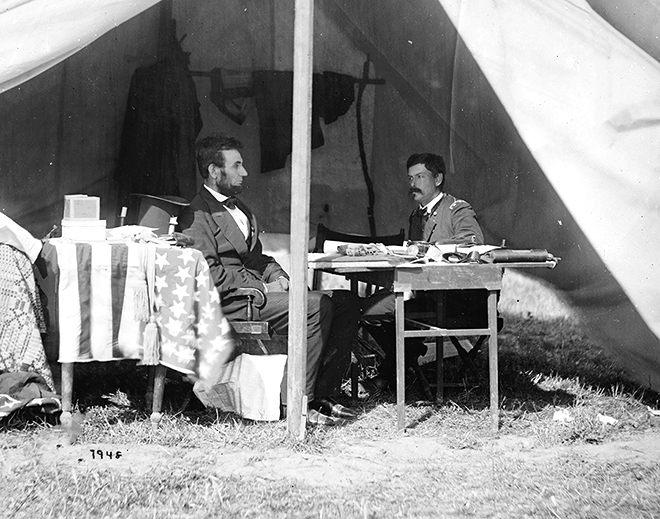

President Lincoln and General George B. McClellan talking in the general’s tent.

President Lincoln and General George B. McClellan talking in the general’s tent.

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, cwpb 0435

Lincoln became frustrated at McClellan’s reluctance to move his force during the Peninsula Campaign. Lincoln attempted to change McClellan’s behavior and bring his actions into conformity with Union battle strategy. It would have been easy for Lincoln to order his subordinate to move the forces, but Lincoln did not want to create an acrimonious situation and realized he had to cultivate this important relationship. McClellan had a delicate tolerance for criticism and was immensely popular with his troops. Instead, Lincoln sent forty-five messages over a four-month period. These messages were clearly reasoned, incredibly patient, and persistent arguments encouraging McClellan to act.[6] Lincoln attempted to use reason and information to push his subordinate and inspire action.

Lincoln displayed discretion in knowing when to order specific action and when to encourage his generals to come to the decision he wanted them to make.

For example, Lincoln wrote:

You know I desired, but did not order, you to cross the Potomac below, instead of above the Shenandoah and Blue Ridge. My idea was that this would at once menace the enemies’ communications, which I would seize if he would permit. If he should move Northward I would follow him closely, holding his communications. If he should prevent our seizing his communications, and move towards Richmond, I would press closely to him, fight him if a favorable opportunity should present, and, at least, try to beat him to Richmond on the inside track. I say “try”; if we never try, we shall never succeed.

[7]

Lincoln displayed discretion in knowing when to order specific action and when to encourage his generals to come to the decision he wanted them to make. Transformational leaders have a clear vision they are able to articulate to followers and help followers experience the same passion and motivation to fulfill the goals of the enterprise.[8] In another example, Lee served McClellan a decisive loss at the Battle of Gaines’ Mill, and McClellan publicly disparaged the President.[9] In response, Lincoln calmly responded by trying to help McClellan to see the overall objective of the war and articulated a compelling vision of the future of the engagement.[10] He did so by allowing McClellan to save face, instead of trying to make an example out of him. The massaging of the relationship sent a message to the Army of the Potomac that the Executive office and military were united in the cause. These acts exemplify Lincoln’s ability to take the “high road” as a transformational leader for the greater good.

Transformational leaders allow their subordinates the room to make mistakes and then learn from those mistakes.

In another example of inspirational motivation, Lincoln gave Grant great latitude in his decision making. Lincoln had approved Grant’s decision to move his army south in three different directions upon taking control of the army in the east.[11] During the battle of Cold Harbor, Grant admitted he had made a mistake in engaging Lee, where no advantage was gained to offset the heavy loss of men.[12] Despite heavy losses, Lincoln supported Grant and urged him on with a telegram stating to maintain his overall vision and exhorting him with, “You will succeed.”[13] Lincoln expressed confidence that Grant could achieve his goals, showing support for his general and his decisions. Transformational leaders allow their subordinates the room to make mistakes and then learn from those mistakes. This allows a subordinate to grow, cultivating the next generation of leaders.

A transformational leader puts the mission ahead of personal ambition.

Idealized Influence

Lincoln showed another component of transformational leadership — idealized influence — as Grant was laying siege to Petersburg and needed more troops. Grant requested Lincoln raise 300,000 additional troops via a draft. The draft, which would be unpopular, would take place prior to the heavily contested 1864 presidential election, and many advised Lincoln to hold off so as not to negatively impact his re-election run.[14] However, Lincoln pressed forward, stating “what is the presidency to me if I have no country.”[15] Lincoln showed enthusiasm about what needed to be accomplished, even though his decision could have a profound personal impact on his career. He understood what it would take to accomplish the mission, setting aside his personal ambitions and potentially losing the presidency. A transformational leader puts the mission ahead of personal ambition. This cultivates an environment that encourages buy-in. Ultimately, accountability in a work environment begins by demonstrating the behavior you want to see modeled by others.

Transformational leaders keep lines of communication open …

Individualized Consideration

Lincoln offered support and encouragement to his subordinates. Transformational leaders keep lines of communication open so subordinates feel free to share ideas and concerns, displaying the third component — individualized consideration. Lincoln maintained a close relationship with Northern soldiers and understood the “hearts and minds of the men in his ranks.”[16] When visiting the battlefields, he made it a point to have small, meaningful conversations with soldiers. He also hosted numerous soldiers at the White House. Lincoln always treated the men with respect and courtesy, regardless of rank.[17] Lincoln patiently received soldiers in the White House, listening to every request and attempting to solve each problem, no matter how insignificant it was.”[18] When he visited soldiers in the hospital, he showed genuine concern for their injuries.[19] Lincoln treated others as individuals, rather than just as members of a group. He understood that individuals have different needs, abilities, and aspirations.[20]

Transformational leaders attempt to engage in the emotional support of their followers and effectively transcend change.

Lincoln’s common touch and absolute absence of affectation won the affection and loyalty of the men.[21] Lincoln’s motivation of his troops is evidenced in a letter from a soldier regarding his reenlistment: “I have made up my mind that a country that is worth living in time of peace is worth fighting for in time of war so I am yet willing to put up with the hardships of a soldiers life.”[22] Robert E. Lee’s plan was not to strike a decisive blow that would win the war outright, but rather, drag out the war with small victories until the North lost the will to carry on.[23] Lincoln’s leadership guided the North and its soldiers through four grueling years of battle, ultimately outlasting the manpower and supplies of the South. His transformational leadership fostered the relationships necessary to see the mission completed. Ideally, a leader wants to create an environment in which everyone in the enterprise has a different role, but everyone’s status is the same.

Transformational leaders not only challenge the status quo, they ferment creativity and encourage subordinates to explore new opportunities to learn and grow.

Intellectual Stimulation

The final tenant of transformational leadership is intellectual stimulation. Transformational leaders attempt to engage in the emotional support of their followers and effectively transcend change.[24] In order to be a leader as an agent of change, Lincoln had to adjust his leadership style. At the outset of the war, Lincoln delegated to military leaders the military strategy and operations in each conflict.[25] However, after the disaster at Bull Run, Lincoln altered his approach. At first, Lincoln began to question the assumptions of his military leaders. However, ultimately, Lincoln realized that to be an agent of change, he needed to turn his full attention to learning military strategy and developing his own ideas that would carry out his national policy.[26] This allowed Lincoln to speak on the same level with commanders. At first, many generals resented a “civilian” telling them how to do their job. But over time, literature suggests the generals came to believe in Lincoln and his strategy. Had Lincoln not diligently studied military strategy and re-defined the role of commander-in-chief, he would not have become the agent of change that ultimately navigated the Union to victory. Transformational leaders not only challenge the status quo, they ferment creativity and encourage subordinates to explore new opportunities to learn and grow.[27]

EXPAND YOUR KNOWLEDGE

External Links to Additional Resources

Lincoln’s greatest legacy as President is how he invoked change and innovation. Lincoln demonstrated this trait on the moral issue of slavery when he penned the Emancipation Proclamation, as an executive order, that changed the legal status of enslaved people.[28] Many advisors were hesitant for Lincoln to explicitly intertwine the war and the issue of slavery, as it might lose support for the war in the North and invoke passions in the South.[29] Lincoln was well aware of this potential problem. Five months prior to the Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln wrote an editorial to Horace Greely in the New York Tribune.[30] In the editorial, Lincoln expressed that his “paramount objective in this struggle [was] to save the Union” and not the issue of slavery.[31] But, then Lincoln extorted that the only way to save the Union was to abolish slavery. Lincoln linked the controversial act of slavery with the incontrovertible idea of saving the Union.[32] By doing so, he laid the groundwork to draw criticism away from slavery and focus attention on the objective of preserving the Union.[33]

One year after writing his editorial, and after the Battle of Gettysburg, Lincoln addressed the nation in what is now known as the Gettysburg Address, stating: “that these dead shall not have died in vain — that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom — and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”[34] Letters suggest that some Northern soldiers still disapproved of freeing the slaves, but for every expression of disapproval for the Emancipation Proclamation “there were ten in support of the act.”[35] Lincoln combined intellectual stimulation and idealized attributes to transform the war from a singular purpose (preserving Union), to a dual purpose (preserving the Union and ending slavery). He did so by first transforming how people think about the issue of slavery, and once doing so, invoking the moral consequences of it.

This final element of leadership turned out to be crucial. Lincoln realized that to win the war, the North would have to relentlessly pursue Lee and his Confederate Army of Northern Virginia. The North maintained an advantage of manpower and resources. Lincoln determined the North had to utilize its resources to engage Lee and the South in a war of attrition. However, Lincoln did not employ generals who either understood, or shared this philosophy (with the notable exception of Grant and Sherman). By learning military strategy, Lincoln learned how to speak on the same level with military commanders, and placed himself in a position as a true Commander in Chief. For example, Lincoln started the practice of issuing General Orders. Lincoln utilized General Orders to facilitate the movement of forces, to execute proposed plans of attack on supply lines, and command the Union forces to engage the enemy.

Further, Lincoln demonstrated intellectual stimulation by issuing the first code of conduct. Lincoln supported Generals Grant and Sherman by urging them to attack and acquiescing to the severity of harm they enacted upon the South. However, Lincoln also disavowed malice toward the enemy or any desire for revenge.[36] To deal with the moral question of cruelty, Lincoln issued General Order 100, known as Lieber’s Code, which provided a written, official, and widely circulated condemnation of many kinds of misconduct and atrocities.[37] Lincoln again combined intellectual stimulation and idealized attributes. Lieber’s Code asked soldiers to consider their own values and beliefs, and consider the moral and ethical consequences of their decisions. The Code was a nontraditional way to re-think ideas that had never formally been questioned. The Emancipation Proclamation and Lieber’s Code established legal precedent, well ahead of its time, that continue to permeate the modern battlespace today. Intellectual stimulation encourages open-mindedness and flexibility. A good leader will use intellectual stimulation to advance a vision that provides focus and purpose to obtain objectives and meet goals.

Transformational leadership can be a guide for our Airmen as we pursue our mission with excellence and integrity to become leaders, innovators, and warriors.

Abraham Lincoln embodied the attributes of a transformational leader. Through his leadership, Lincoln constructed a vision not only for the preservation of the Union, but opened a pathway to a reconstructed union without malice or desire for revenge. Through his actions, Lincoln encouraged his soldiers to meet goals, while maintaining moral integrity — and commanded an entire nation to do the same. Lincoln’s presidency is a case study in how to effectively employ a transformational leadership style. When used appropriately, transformational leadership can be a highly effective managerial style. The mission of the United States Air Force is to fly, fight, and win in air, space, and cyberspace. Transformational leadership can be a guide for our Airmen as we pursue our mission with excellence and integrity to become leaders, innovators, and warriors.

National Geographic / History Channel Documentary:

Abraham Lincoln: American Mastermind (1:03:00)

About the Author

Major Michael A. Schrama, USAF

Special Assistant to the United States Attorney General, Environmental and Natural Resource Division, United States Department of Justice, Washington, D.C. Barred in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Education: Bachelor of Arts (English), Georgetown University; Masters of Science (Education), Lehman College; Juris Doctor, Roger Williams School of Law; Master of Military Operational Art and Science, Joint Warfare Concentration, Air Command and Staff College (OLMP); Master of Laws (Government Procurement and Environmental Law), The George Washington University School of Law.

[1] Kelly Knauer, Abraham Lincoln: His Life and Times: An Illustrated History 88 (2009).

[2] Richard Bolden, Jonathan Gosling, Antonio Marturano, & P Dennison, A Review of Leadership Theory and Competency Frameworks 5 (2003).

[3] Id.

[4] Gordon Leidner, Lincoln the Transformational Leader, Lincoln Herald, Fall 2002, at 111.

[5] Knauer, supra note 1, at 88-89.

[6] William Miller, President Lincoln, The Duty of a Statesman 179 (2008).

[7] Letter from Major General George McClellan to President Abraham Lincoln (Oct. 13, 1862) (on file with Dickinson College Civil War Research database).

[8] Bernard M. Bass & Ronald E. Riggio, Transformational Leadership 64 (2nd ed. 2006).

[9] Miller, supra note 6, at 179.

[10] Id.

[11] Doris Goodwin Kearns, Team of Rivals 618 (2005).

[12] Miller, supra note 6, at 359.

[13] Id.

[14] Id. at 372.

[15] Id. at 373.

[16] Leidner, supra note 4.

[17] Id.

[18] Id.

[19] Id.

[20] Bolden, Gosling, Marturano, & Dennison, supra note 2, at 5.

[21] Leidner, supra note 4.

[22] Id.

[23] Ron C. Chernow, Grant 355-56 (2017).

[24] Bolden, Gosling, Marturano, & Dennison, supra note 2, at 5.

[25] Ronald C. White, Jr., A. Lincoln 437 (2009).

[26] Id. at 438.

[27]Bass & Riggio supra note 8, at 7, 56.

[28] Emancipation Proclamation (Jan. 1, 1863), Presidential Proclamations: 1791-1991, Record Group 11, Gen. Records of the U.S. Gov’t Nat’l Archives, http://www.let.rug.nl/usa/presidents/abraham-lincoln/the-emancipation-proclamation-1863.php (last visited May 9, 2018); https://www.archives.gov/exhibits/featured-documents/emancipation-proclamation (last visited June 14, 2018). (Proclamation 95 declared “that all persons held as slaves” within the rebellious states “are, and henceforward shall be free.”)

[29] Kearns, supra note 11, at 478.

[30] Letter from President Abraham Lincoln to Horace Greeley (Aug. 20, 1862) (on file with Dickinson College Civil War Research database).

[31] Id.

[32] Leidner, supra note 4.

[33] Id.

[34] Kearns, supra note 11, at 584

[35] Id

[36] Miller, supra note 6, at 363.

[37] Francis Lieber, Instructions for the Government of the Armies of the United States in the Field 186 (1st ed. 1863), https://archive.org/details/governarmies00unitrich (last visited May 24, 2018). (Lieber’s Code was the first of its kind and has influenced similar codes since.)